The Great War In Southend's Skies

The War Office had included the field at Rochford (now the site of Southend airport) in a list of potential airfields as early as 1914.(2*) They had good reasons for considering the site; the fields were flat and well drained, the railway line came within close proximity for bringing in supplies, and it was situated on the estuary and therefore in an ideal location for the defence of London. The area also had an operational telephone network, a feature which would become invaluable in the face of multiple night-time air raids throughout the first world war.

At the start of the war the British military hadn't yet created an air force as an independent organisation. Instead the use of aircraft was split between the two divisions of the armed forces with the Royal Flying Corp being the Army's aviators, whilst the Royal Naval Air Service served the Navy's flying needs. It was only towards the end of the war in April of 1918, that the two services would become merged into what we now know as the Royal Air Force. In the early part of WWI, it was the RNAS which was given responsibility for flying home defence patrols, whilst the RFC was predominately posted overseas on the Western front.

It is reported on a website covering local history, that in December of 1914, Southend received the very first air raid in the country in the form of a single bomber which purportedly dropped 'rust rivets' on the town as it flew overhead. I've been trying to look for other sources for this, but was unable to find any references to either the attack or indeed what on earth rust rivets actually are! (I've assumed they are perhaps rusty nails which could be trodden on to cause an infection, but this is an uneducated guess.) I'll continue to keep my eye out for sources on this - not that I disbelieve the story, but I would like to err on the side of caution before stating unequivocally that this occurred.

As the war in Europe worsened and more volunteers from Essex joined the armed forces, Southend began getting its first unfiltered descriptions of the frontlines through personal correspondence. Whilst the bulk of the population no doubt joined the regular army, a smaller number sought a more novel experience in the relatively new RFC on the Western front. One story, retold through the Southend and Westcliff Graphic from the January 1st, 1915 issue, gives the account of a Corporal Oscar H. Bowmaker, (son of a manager for the Mascot cinema that was once on London Road in Westcliff) and how they celebrated the Christmas of 1914:

"I received a Christmas pudding from Ethel (his sister). I warmed the same in the following manner with the following implements: (1) an oil drum, (2) a jam tin, (3) a petrol tin, (4) -an ordinary army canteen, (5) some bits of wire. With the oil drum I made a fire place, the wire forming the fire-bars, the jam tin filled with petrol was the fire, the petrol tin the boiler, and the army canteen the steamer. We get a rum issue every night, and last night two of us saved our issue and set fire to the pudding with it. Taking all things into consideration the whole thing turned out a howling success, and I am looking forward to repeating the offence when I receive your box. Strange to say I came across two brothers from Southend, and more strange still they used to live only a few doors from us. It certainly does seem a bit remarkable there should be three Southenders in the same squadron considering that a squadron is only just over 100 strong."(3*)

In January of 1915 the first zeppelin raids began on the British isles when Zeppelin L3 and L4 bombed Yarmouth and Kings Lynn killing four people; marking the beginning in a series of airship raids that would continue over the course of the war. At the start of the war the Germans already had a sizable fleet of airships built by both Zeppelin and Schutte-Lanz, and despite their fragility, the altitude at which these aircraft could fly put them well out of range of British anti-aircraft guns and the early aeroplane designs which had been tasked with home defence. With a huge range and a radio which could reach back to their launch facilities in Belgium, they became a real menace for the British and it took some time for defensive tactics to come to fruition. Although the airships themselves were difficult to navigate and even more difficult to aim ordinance with, their vast sizes (their lengths often approached 200m,) meant their psychological impact on the civilians in the UK far outweighed their strategic importance.

Up until May of 1915, the Kaiser (the German King) interestingly had felt that there should be an agreement between Britain and Germany over the use of aircraft in bombing raids over civilian areas. In an attempt to keep civilian casualties to a minimum, the airships were originally ordered to only commit raids on military targets and that attacks on London should be avoided.(4*) Following a British air raid on the Kaiser's headquarters on the Western Front at Ludwigshaften however, that order was repealed; leading ultimately to the approval of bombing raids on London, but still with the specific instruction that damage to royal palaces and residential areas should be kept to a minimum.

On May 10th 1915, Southend was to see its first aerial bombings of the war. Zeppelin LZ38, commanded by Hauptmann Erich Linnarz, had been tasked with the mission of providing reconnaissance of the Thames estuary area - given that it was a great navigational aid for performing raids on the capital. After getting as far as Pitsea at which point anti-aircraft guns opened fire from a gun battery on Canvey Island(6*), LZ38 turned back and traveled on towards Southend, and presumably after noting the large number of ships docked off of and around the pier-head, decided the town made a viable secondary target.(5*) (Of course, had the captain realised those ships were in fact predominately full of German POWs, he perhaps wouldn't have been so eager to attack!)

Roughly one hundred and fifty incendiary and explosive bombs and were dropped on Southend that night, damaging a number of residential properties all over the area including Southend, Westcliff, Leigh and Canvey Island. Amazingly, (likely owing to the fact that many bombs failed to detonate,) only one death from the raid was recorded after a bomb made a direct hit on a house in North Road (number 120), killing the occupant, a Mrs. Whitwell, after the bomb landed on her as she lay in bed. The first bomb of the raid reportedly landed in York Road, shattering the windows on the street and causing a Corporal Hanney who was billeted in one of the houses to be "peppered" with shards of glass in his face as he slept in the room with his wife and young child.(11*)

A number of fires spread throughout the area whilst the fire service frantically tried to deal with them, however by eight-o-clock the following morning eighty bombs had been recovered and taken to the police station (its unclear whether these are bombs which failed to detonate, or whether these are solely the spent incendiary bomb cartridges.) As the Zeppelin left in the early hours the following morning, two local RNAS fighters were scrambled to try and pursue LZ38, but a thick band of cloud prevented any retaliation.(12*)

It was noted in the local paper that German radio broadcasts announced shortly after that the Zeppelin had attacked "the fortified town of Southend", a term which The Southend and Westcliff Graphic branded "the usual German lie". However, it has to be said that given the number of military personnel, shipping, and anti-aircraft guns in the area (not to mention the garrison at Shoebury,) the Germans did kind of have a point, even if their aim on those targets was shockingly bad. The whole ordeal of this first raid on the town is explained in great detail in the local paper for that week, I've made the PDF of it available for you to read in its entirety here. As LZ38 left, a note was dropped which read "You English. We have come and will come again. Kill or cure."(7*)

Directly after the attack a number of residents reacted in anger towards local German businesses, the windows of a furniture shop in Queens Road and a Tobacconist and hairdressers in the High Street was pelted with stones and shot at with a revolver! Soldiers garrisoned in the town showed up and acerbated the situation by shouting words of encouragement to a crowd which was already incensed into action; it was only the threat of harsh punishment from both the police and army officers that finally convinced the crowds and soldiers to return home. Despite the scenes only two arrests were made and nobody was seriously injured.

The crew of the LZ38 kept their promise to return, and a few weeks later on the 25th of May, arrived at Southend via Shoebury at a high altitude; this time under heavy anti-aircraft fire from the start. Despite the gunfire though, the Zeppelin still managed to deliver seventy or so bombs, killing a civilian, and causing injury to several others before eventually slinking back off into the darkness of the North sea some hours later.

Its likely that the two raids on Southend are what prompted the War Office to finally consider the opening of an airfield at Rochford. In May of 1915, the RNAS who at this point in the war were tasked with home defence, were moved from Lydd to Rochford. Within hours of their arrival, the RNAS had erected some basic hangers, beginning the site's official use as an airfield.(1*) It would become the largest airfield in Essex, and received the greatest number of units throughout the war (although that is presumably on account that many of units did basic training there.) The first sortie flown out of Rochford airfield would come only a few days after the station's official opening on the 31st of May, as LZ38 returned yet again, this time as she made her way towards London. She was spotted just off Margate at around 9:40pm, and later just north of Shoebury. At 10:20pm, Sub. Lt A. W. Robertson took off from Rochford airfield in his Bleriot Parasol(13*) and slowly began climbing to engage the Zeppelin. As he reached 6000ft, and LZ38 came into view, the Bleriot's engine began to misfire and so Robertson was forced to land on the Leigh marshes (I presume what we today call Two-Tree Island.) Both pilot and aircraft survived, and the following day ground crews arrived to take the aircraft to the nearby Rochford.(8*)

LZ38 went on unhindered to London, killing a number of civilians, however the war was soon over for her as on the 7th of June 1915, RNAS aircraft succeeded in successfully destroying her as she returned to her hanger at Evere in Belgium. A few hours later its sister ship LZ37, was also shot down by RNAS aircraft - and as a result, at least for a time, there was some respite from the Zeppelin raids on England.(9*)

The next entry on Rochford's rosters came a while later on the night of the 31st of January 1916, when nine Zeppelins departed en masse from Belgium with the intention of raiding Liverpool. Bad weather and engine problems hindered the German attack throughout the night, and despite eight of the nine captains returning the day later, not one in fact had hit Liverpool. Most of the bombs fell on random leafy suburbs like the account from Wednesbury just north of Birmingham.

Getting reports of these multiple Zeppelins over the south east coast, Sub. Lt J. E. Morgan took off from Rochford airfield at 20:43 in his B.E.2c and began climbing to a decent altitude.(14*) As Morgan reached 6400ft however, his engine began to misfire and the aircraft was finding it increasingly difficult to climb further, but as Morgan looked about in the darkness he; "saw a row of lighted windows... something like a railway carriage with the blinds down" about 35 yards ahead. Acting quickly, he fired a volley of several rounds from his service revolver before the lights seemed to rapidly rise up next to him. Thinking he had suddenly entered into a dive the pilot glanced at his instruments and realised that it had in fact been a Zeppelin which had likely dropped ballast in order to escape the defending fighter aircraft.

At the start of the war the British military hadn't yet created an air force as an independent organisation. Instead the use of aircraft was split between the two divisions of the armed forces with the Royal Flying Corp being the Army's aviators, whilst the Royal Naval Air Service served the Navy's flying needs. It was only towards the end of the war in April of 1918, that the two services would become merged into what we now know as the Royal Air Force. In the early part of WWI, it was the RNAS which was given responsibility for flying home defence patrols, whilst the RFC was predominately posted overseas on the Western front.

It is reported on a website covering local history, that in December of 1914, Southend received the very first air raid in the country in the form of a single bomber which purportedly dropped 'rust rivets' on the town as it flew overhead. I've been trying to look for other sources for this, but was unable to find any references to either the attack or indeed what on earth rust rivets actually are! (I've assumed they are perhaps rusty nails which could be trodden on to cause an infection, but this is an uneducated guess.) I'll continue to keep my eye out for sources on this - not that I disbelieve the story, but I would like to err on the side of caution before stating unequivocally that this occurred.

As the war in Europe worsened and more volunteers from Essex joined the armed forces, Southend began getting its first unfiltered descriptions of the frontlines through personal correspondence. Whilst the bulk of the population no doubt joined the regular army, a smaller number sought a more novel experience in the relatively new RFC on the Western front. One story, retold through the Southend and Westcliff Graphic from the January 1st, 1915 issue, gives the account of a Corporal Oscar H. Bowmaker, (son of a manager for the Mascot cinema that was once on London Road in Westcliff) and how they celebrated the Christmas of 1914:

"I received a Christmas pudding from Ethel (his sister). I warmed the same in the following manner with the following implements: (1) an oil drum, (2) a jam tin, (3) a petrol tin, (4) -an ordinary army canteen, (5) some bits of wire. With the oil drum I made a fire place, the wire forming the fire-bars, the jam tin filled with petrol was the fire, the petrol tin the boiler, and the army canteen the steamer. We get a rum issue every night, and last night two of us saved our issue and set fire to the pudding with it. Taking all things into consideration the whole thing turned out a howling success, and I am looking forward to repeating the offence when I receive your box. Strange to say I came across two brothers from Southend, and more strange still they used to live only a few doors from us. It certainly does seem a bit remarkable there should be three Southenders in the same squadron considering that a squadron is only just over 100 strong."(3*)

The Beginning of the Zeppelin Raids

In January of 1915 the first zeppelin raids began on the British isles when Zeppelin L3 and L4 bombed Yarmouth and Kings Lynn killing four people; marking the beginning in a series of airship raids that would continue over the course of the war. At the start of the war the Germans already had a sizable fleet of airships built by both Zeppelin and Schutte-Lanz, and despite their fragility, the altitude at which these aircraft could fly put them well out of range of British anti-aircraft guns and the early aeroplane designs which had been tasked with home defence. With a huge range and a radio which could reach back to their launch facilities in Belgium, they became a real menace for the British and it took some time for defensive tactics to come to fruition. Although the airships themselves were difficult to navigate and even more difficult to aim ordinance with, their vast sizes (their lengths often approached 200m,) meant their psychological impact on the civilians in the UK far outweighed their strategic importance.

Up until May of 1915, the Kaiser (the German King) interestingly had felt that there should be an agreement between Britain and Germany over the use of aircraft in bombing raids over civilian areas. In an attempt to keep civilian casualties to a minimum, the airships were originally ordered to only commit raids on military targets and that attacks on London should be avoided.(4*) Following a British air raid on the Kaiser's headquarters on the Western Front at Ludwigshaften however, that order was repealed; leading ultimately to the approval of bombing raids on London, but still with the specific instruction that damage to royal palaces and residential areas should be kept to a minimum.

|

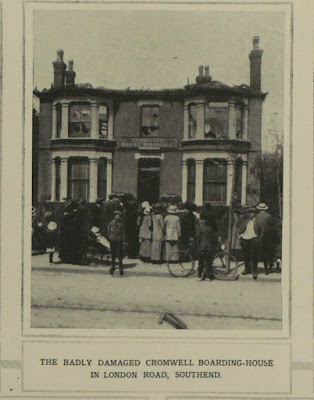

| Cromwell Boarding house on London Road after being damaged by the May 10th Zeppelin raid. |

On May 10th 1915, Southend was to see its first aerial bombings of the war. Zeppelin LZ38, commanded by Hauptmann Erich Linnarz, had been tasked with the mission of providing reconnaissance of the Thames estuary area - given that it was a great navigational aid for performing raids on the capital. After getting as far as Pitsea at which point anti-aircraft guns opened fire from a gun battery on Canvey Island(6*), LZ38 turned back and traveled on towards Southend, and presumably after noting the large number of ships docked off of and around the pier-head, decided the town made a viable secondary target.(5*) (Of course, had the captain realised those ships were in fact predominately full of German POWs, he perhaps wouldn't have been so eager to attack!)

Roughly one hundred and fifty incendiary and explosive bombs and were dropped on Southend that night, damaging a number of residential properties all over the area including Southend, Westcliff, Leigh and Canvey Island. Amazingly, (likely owing to the fact that many bombs failed to detonate,) only one death from the raid was recorded after a bomb made a direct hit on a house in North Road (number 120), killing the occupant, a Mrs. Whitwell, after the bomb landed on her as she lay in bed. The first bomb of the raid reportedly landed in York Road, shattering the windows on the street and causing a Corporal Hanney who was billeted in one of the houses to be "peppered" with shards of glass in his face as he slept in the room with his wife and young child.(11*)

|

| Children sitting in a bomb crater in Ambleside Drive, Southchurch, on the day after the May 10th Zeppelin raid. |

A number of fires spread throughout the area whilst the fire service frantically tried to deal with them, however by eight-o-clock the following morning eighty bombs had been recovered and taken to the police station (its unclear whether these are bombs which failed to detonate, or whether these are solely the spent incendiary bomb cartridges.) As the Zeppelin left in the early hours the following morning, two local RNAS fighters were scrambled to try and pursue LZ38, but a thick band of cloud prevented any retaliation.(12*)

It was noted in the local paper that German radio broadcasts announced shortly after that the Zeppelin had attacked "the fortified town of Southend", a term which The Southend and Westcliff Graphic branded "the usual German lie". However, it has to be said that given the number of military personnel, shipping, and anti-aircraft guns in the area (not to mention the garrison at Shoebury,) the Germans did kind of have a point, even if their aim on those targets was shockingly bad. The whole ordeal of this first raid on the town is explained in great detail in the local paper for that week, I've made the PDF of it available for you to read in its entirety here. As LZ38 left, a note was dropped which read "You English. We have come and will come again. Kill or cure."(7*)

|

| An example of the anti-aircraft guns of the time. This one was based at Ramsden near Hanningfield. |

The crew of the LZ38 kept their promise to return, and a few weeks later on the 25th of May, arrived at Southend via Shoebury at a high altitude; this time under heavy anti-aircraft fire from the start. Despite the gunfire though, the Zeppelin still managed to deliver seventy or so bombs, killing a civilian, and causing injury to several others before eventually slinking back off into the darkness of the North sea some hours later.

Its likely that the two raids on Southend are what prompted the War Office to finally consider the opening of an airfield at Rochford. In May of 1915, the RNAS who at this point in the war were tasked with home defence, were moved from Lydd to Rochford. Within hours of their arrival, the RNAS had erected some basic hangers, beginning the site's official use as an airfield.(1*) It would become the largest airfield in Essex, and received the greatest number of units throughout the war (although that is presumably on account that many of units did basic training there.) The first sortie flown out of Rochford airfield would come only a few days after the station's official opening on the 31st of May, as LZ38 returned yet again, this time as she made her way towards London. She was spotted just off Margate at around 9:40pm, and later just north of Shoebury. At 10:20pm, Sub. Lt A. W. Robertson took off from Rochford airfield in his Bleriot Parasol(13*) and slowly began climbing to engage the Zeppelin. As he reached 6000ft, and LZ38 came into view, the Bleriot's engine began to misfire and so Robertson was forced to land on the Leigh marshes (I presume what we today call Two-Tree Island.) Both pilot and aircraft survived, and the following day ground crews arrived to take the aircraft to the nearby Rochford.(8*)

|

| An example of a RNAS Bleriot as flown by Robertson. |

The Night Time Patrols

|

| A Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.12a, one of the variants of aircraft that would have regularly conducted night patrols out of Rochford airfield. |

Getting reports of these multiple Zeppelins over the south east coast, Sub. Lt J. E. Morgan took off from Rochford airfield at 20:43 in his B.E.2c and began climbing to a decent altitude.(14*) As Morgan reached 6400ft however, his engine began to misfire and the aircraft was finding it increasingly difficult to climb further, but as Morgan looked about in the darkness he; "saw a row of lighted windows... something like a railway carriage with the blinds down" about 35 yards ahead. Acting quickly, he fired a volley of several rounds from his service revolver before the lights seemed to rapidly rise up next to him. Thinking he had suddenly entered into a dive the pilot glanced at his instruments and realised that it had in fact been a Zeppelin which had likely dropped ballast in order to escape the defending fighter aircraft.

Having lost the object and his own bearings, Morgan began a controlled descent to the west and fired off a flare from his flare gun (which was seen by the gun crews on Southend pier) hoping that one of the local airfields might fire one back in response so he might find someplace to land. At 3000ft a blur of light shone through a break in the cloud and, descending to 300ft, found a large steamer in the Thames. Circling three times, the pilot signalled to the ship with morse code requesting a bearing back towards Southend but no response came back, probably because the ship was Dutch! He had however got a response he didn't want as the flashing lights of his signals had been spotted by an anti-aircraft battery at Thameshaven which had opened fire, apparently unaware of friendly air activity that night.(15*)

Glimpsing some nearby coastline in the light of a sweeping searchbeam, Morgan expertly set down his BE2c on the marshes at Thameshaven (to the south of Corringham) achieving a perfect landing. The following afternoon the aircraft was flown back to Rochford.(10*) This kind of account is not uncommon for those tasked with flying night patrols. They were basically done blind with no on board radios, limited visibility and in aircraft of questionable reliability.

L19, the only Zeppelin not to make it back that night came down in the North Sea after three of its four engines had failed. It is thought that as it floundered without power, Dutch anti-aircraft fire had ruptured its gas cells. An English trawler had come across the airship a day later as she was partially submerged with sixteen of the crew members clinging on to the hull for dear life, but fearing that the German's could overpower the trawler's crew, they refused to rescue the stranded men. Subsequently the men were left to their fate, and all sixteen German crew members were eventually drowned.

On the 31st of March another large German Zeppelin raid was mounted on Britain, this time with London being the main target. Initially seven airships left their bases in Belgium, but two dropped out leaving the remaining five to continue on with their mission. The five airships all came off the North sea on a south west heading from over the Folkestone area. Just like the large raid beforehand however, not one airship reached the main target of London. Instead their payloads appear to have been dropped at random with Sudbury, Braintree, Doddinghurst, Blackmore, Springfield, Stanford Le Hope, Bury St Edmunds and Thameshaven all having being struck. Zeppelin L15, one of the five marauders, would not get away with their actions though and would be her third and final attack on Britain since the war had started, in addition to eight reconnaissance missions under the command of Joachim Breithaupt and his crew.

Breithaupt's bad set of circumstances began as soon as she reached the English coast over Great Yarmouth as the crew was taken by surprise by the newly installed anti-aircraft batteries in the area. She was caught in the searchlights and was put under heavy fire prompting the crew of L15 to drop their ballast and climb to the height of 10,000ft. Having risen to such an altitude though, navigation was now an issue and with cloud preventing a view of the land below, the crew dropped a gondola and some 'light bombs' to help ascertain their position. (Some of the zeppelins were equipped with a gondola that could be hung hundreds of feet below the airship's hull by means of cable, and communicated with the bridge via a telephone cable.)

By 9pm L15 was passing Witham and heading towards Pitsea and after finally catching a glimpse of the Thames on the horizon, was readying themselves to follow the river to the main target of London. However the craft's engines began to fail and without any additional ballast to drop, keeping level flight was becoming an issue. Disaster struck the Zeppelin as searchlights operating out of Dartford found their quarry at around 9.40pm, prompting multiple local guns to commence firing all at once. In an attempt to escape the bombardment, Breithaupt ordered the airship to head north away from the gun batteries and in an attempt to climb higher, jettisoned the majority of bombs which thankfully landed harmlessly in a field in Rainham. After five minutes of constant bombardment however, the British guns finally did some damage as shrapnel shredded a large hole in the side of L15's hull and caused three of the gas cells to become punctured and deflate.(16*) Struggling to keep altitude she drifted towards Ingatestone where ten minutes after being struck by the Purfleet battery, where a BE2c aircraft piloted by 2nd Lt. Albert De Bath Brandon had become aware of L15 in the searchlights and in among the commotion of gunfire.

Continuing on, and still struggling to get rid of excess weight, the remaining bombs were allegedly dropped on Belfairs golf course, one bomb crater according to Mr Aylen's account still remains at the golf course on the 14th fairway. Alongside the bombs, all but four hours worth of fuel was dropped as well as engine shrouds, exhaust manifolds and even a Luger was found around Belfairs in the years afterwards!

By 11:55, L15 had come to a grinding halt remaining stationary above what is now the Elms public house. At just a few hundred feet up, the locals on the ground could hear the Germans shouting to one another as they struggled to get the engines back online, prompting many of the locals to begin jeering and shouting abuse up at the airmen above. As the airship remained stationary, an RFC BE2c flown by Sub Lt G. L. F. Stevens arrived on scene, but perhaps after realising the built up area below, decided not to attack. His report afterwards mentioned that he had been driven away by gunfire from the Zeppelin, but that would be pretty difficult considering the Zeppelin crew had already thrown all their machine guns overboard! The real reason as to why he didn't engage might have something to do with the fact that Steven's parents lived not too far away!

Initially there had been a prize of £500 offered to the first crew members to successfully take down zeppelins, but given that so many men had played a part in L15's destruction, it left the issue that many men were claiming at least some partial credit. In the end, multiple medals were forged instead of the cash prize as a thank you to the multiple individuals who had had their own part to play. Whilst this story sounds great, especially from a local perspective - I must make clear that Mr. Aylen's booklet is the only written account I have come across which mentions the bombing of Eastwood and Belfairs, so please be wary before taking this story as gospel.

On June 5th 1917, an attack by German Gotha bombers on Sheerness directly opposite Southend on the south bank of the Thames estuary, once again meant that a few of the local fighters from Rochford were deployed against the enemy. A BE2d, a BE12a and Captain Cooke now supplied with a somewhat more efficient Sopwith Strutter, were thrown up again to begin the daunting task of bomber hunting. During the course of the engagement, one Gotha was shot down by ground fire from batteries on Sheerness and Shoeburyness, with the bomber landing and sinking at around 18:30 hours just a few miles off Barton's Point. Both the pilot and observer died as a result of the crash, however the gunner survived with only a broken leg. Blown out of proportion, the British papers hailed it a great victory;

The Daily Telegraph wrote "So efficient were the defences that they only succeeded in penetrating the coastal districts for a few miles, and after dropping their bombs made off at high speed". Strangely, the The Express went further, claiming that half of the bombers in the raid had been wiped out. Of course this was completely made up, and should really serve as a stark reminder to us today of the power of propaganda! In truth, the Germans only lost one aircraft which they admitted to, and that had been simply the case of a lucky anti-aircraft gun shot.(21*)

No.37 Squadron, partially based in Rochford. claimed a kill on a Zeppelin on the 16th of July, 1917. Zeppelin L48 had set out with the intention of bombing London with three others, but after being buffeted by bad weather conditions, decided to redirect its attack on the port of Harwich. Unbeknown to the L48's crew however, the British were aware of its general location by monitoring the German radio transmissions and were busy coordinating a counter attack. Experiencing engine difficulties, L48 drifted helplessly towards Orfordness near Felixstowe, right above an experimental RFC airbase that was responsible for testing new and modified aircraft.

Despite being without power and above enemy military installations, L48 was still safe at its extreme altitude, but their time was quickly running out. Experimental BE2c aircraft operating out of Orfordness were given the order to take off and attack the Zeppelin directly overhead, but despite being able to fire off a few drums of ammunition from below, they were unable to climb high enough to engage properly. At around 2am, No.37 Squadron received a phone call requesting support, to which a total of six aircraft, including four from Goldhanger and two from Rochford, responded.

Having eventually got their engines running again, L48 limped onwards towards its target at Harwich, bombing the nearby village of Falkenham shortly before being caught in the searchlights and the aim of local gun fire. Lt. P Watkins, a Canadian born pilot with No.37 Squadron who had only recently been transferred to Home Defence from the Western Front, eventually caught up with L48 as her crew frantically tried to descend as they searched for stronger winds that might carry them away from the barrage of gunfire. In the darkness, the crew presumed that they were heading east back out to sea, but had in fact drifted further north due to their compass freezing in the extreme temperatures. Firing a volley of incendiary and explosive rounds, Watkins was credited with the final kill ending in a blazing wreckage which was said to have been seen up to fifty miles away. The wreckage landed at a farm at Theberton, killing all of the sixteen crew members on board. It is theorised that the multiple mistakes the crew had made that led to their demise, may have been caused by hypoxia.

From humble beginnings, the airfield at Rochford gradually grew to become one of the biggest aerodromes in the country. Multiple home defence and training flights were stationed on site, and the airfield was often used as a stop off for aircraft to refuel at as they traveled to France from their factories in the UK.(24*) The station was a hive of activity, with another home defence Squadron (No.61) equipped with Sopwith Pups, also formed at Rochford by the 2nd of August 1917.

One of the most famous airmen to operate out of Rochford airfield was Cecil Lewis, the author of the autobiographic work Sagittarius Rising which details well the life of a WWI fighter pilot. He wrote of Rochford airfield at that time saying; "No.61 Squadron, to which I had been transferred, was quartered on one side, while up at the other end were a couple of training squadrons".

"My memories of that year at Rochford are crowded. Something always seemed to be happening."(25*)

One of the activities going on at the airfield according to the account of Cecil Lewis was the testing of wireless sets of different varieties for use with recon and fighter aircraft. Whilst these tests were likely first conceived out of the experimental base at Orfordness near Felixstowe, they became more regularly attached amongst the home defence squadrons. A number of Squadrons, including No.37, received BE12s equipped with 'radio trackers' which were meant to track the location and number of enemy aircraft in the darkness of the night. They were however pretty useless as their range was so short. That being said, its strange to think that the first rudimentary night fighter with a primitive "RADAR" was operating as early as August 1917 from Rochford!

The experimental Martinsyde F1 aircraft also flew combat trials from the airfield, and had the rather eccentric design of having the pilot sat behind a gunner who would practically lie down in order to fire a gun upwards into enemy aircraft. Whilst it does sound silly, the design does have its merits. During WWII, German bomber hunter aircraft had what was called Schräge Musik, which was basically upwards firing autocannons - it seems perhaps these designs were in some ways ahead of their time.

Other experimental activity at Rochford included two "ears" which were essentially listening posts made from acoustic mirrors. Spaced three miles apart from one another and combined with large spotlights, the idea was that the sound of incoming aircraft could roughly triangulate the location of enemies at the point at which the spotlights converged - so friendly fighters might stand a chance of finding and engaging in the dark.

As shocking as they were, the Zeppelin raids on Southend a few years previous were far from the worst attacks to hit Southend during the first world war. On the 12th of August 1917, an attack by a flight of Gotha bombers struck Southend town centre, predominately centred around the Victoria railway station on a Sunday evening. The attack killed a total of thirty-two people, including nine children, and forty-three were injured.

Whilst the common belief is that London was initially the primary target for the raid, it had in fact been intended for the naval base at Chatham in Kent. Southend and Margate were considered secondary targets should they fail to reach the primary. With it being a Sunday evening, the number of bombers available for the raid was not as high as it could have been, and out of the thirteen aircraft which left their base in Belgium two in fact had turned about due to engine problems. Strong winds had taken the Gothas farther north than they had intended, and when they turned south west over Clacton to alter their course against the wind at 17:20, they found themselves struggling against a strong headwind.

The local air defences had been alerted to the presence of German bombers and by 17:15 the orders to patrol had been given. However the belief that London was the target had meant most of the patrols were aimlessly hanging around the Hainault and Hornchurch area. The only Squadron which really saw any action that day was No.61 Squadron, which spotted the Gothas heading south west over Burnham, and despite being given no official order to take off by Home Defence, they were granted permission to engage by 61 Squadron's commanding Officer Major E. R. Pretyman.(27*)

One of the Gothas left the formation at around 17:40 and began heading towards the secondary target at Margate, but shortly before reaching Canvey Island the flight leader Oberleutnant Richard Walter realised that carrying on for much longer over enemy territory with strong winds was a bad idea. With two shots of green flares from his flare pistol, he signaled to the rest of the available aircraft to circle around and commence an attack on Southend, which they carried out all too well. An aircraft from No.198(D) Squadron flying thousands of feet below the Gothas attributed their attack on Southend to them sighting a large number of Sopwith Pups readying and taking off below at Rochford airfield - however its just as likely, given fuel restraints, that Southend was the only viable option remaining.

The nine enemy aircraft dropped their altitude before engaging in a sustained attack which created much devastation across the local area. Bombs were dropped on Rochford airfield, narrowly missing hangers belonging to No.61 Squadron, but the vast majority of the enemy bombs fell on civilians all across town. The greatest number of civilians were killed when bombs landed on a path in Victoria Avenue and the Southend High Street. The streets were busy with locals and visitors as many were returning to the railway station as it got later in the evening.

Bombs landed near Lord Roberts Avenue in Leigh-On-Sea, close to a restaurant, but thankfully failed to detonate. In Cliffsea Grove in Leigh, three houses were completely gutted and three more seriously damaged; Special Constable Heap who had been doing his rounds was thrown from his bicycle by the resulting shockwave, but remarkably survived unscathed. Several bombs landed in Westcliff, with one causing damage to homes in Imperial Avenue. Some of the bombs, like one which landed next to a Red Cross Hospital emitted yellow fumes and covered the road in yellow powder prompting much anxiety about its possible toxicity.

Homes in Milton Street and Guildford Road in central Southend were also hit causing multiple fatalities, and two more fell in Lovelace Gardens in Southchurch destroying a home and killing a mother and daughter as they were sat down for dinner. The father who was also sat at the dinner table, either fortunately or unfortunately depending on how you assess the sad nature of the situation, survived.

A horse belonging to a greengrocer in Leigh Road died after being struck by shrapnel from a bomb which detonated in Grasmere Avenue, and a dog was also killed in Sunningdale Avenue (near Chalkwell Hall Junior School.)

It seems the attack was mostly conducted in a straight flight which began in Leigh and ended around Chalkwell in a hurried manner. In the local paper The Southend and Westcliff Graphic in the August 17th issue says "the haphazard way in which the bombs were dropped points to the fact that the enemy planes were making a hurried departure after being encountered by British aeroplanes to the north of the town. The raiders, who numbered nine, disappeared from view over the sea at a considerably greater height than when they were over the town."

It is possible that they dropped their altitude to increase the speed at which they could conduct the attack - and thus get away faster. The low altitude had certainly taken the town by surprise. A witness of the attack in The Southend and Westcliff Graphic" gave the account of what they had seen and felt. "I was at my home in Victoria Avenue, in the garden at the time. When the enemy planes arrived I - and I believe everybody else - took them for our own machines, because they were flying so low. Nobody thought of taking any notice of them until the bombs began to drop, and then it was too late, but there was no panic".

One account which is quite comical given the seriousness of the situation, comes from another resident after their house was peppered in vegetables from the local allotment; "The greatest part of somebody's allotment was transferred into my back bedroom. When the raid was over, and I emerged from my shelter under the stairs, I found every window in my house broken, all the doors blown open, and vegetables scattered all over my back rooms, by a bomb dropped fifty yards away. The place was full of suffocating sulphurous smoke. The noise was terrifying, and yet my little son slept through it all".

As the bombs were falling on Southend, the single bomber which had split off for Margate had encountered no less than nine RNAS fighter aircraft on a routine patrol. Miraculously for the bomber crew however, despite being shot at multiple times (the RNAS records of how much ammunition was used amounted to a total of 1,100 rounds fired at this single Gotha) the pilot managed, despite only running on a single engine, to bring their craft down in a controlled crash landing near Ostende in Belgium without losing a single crew member.(26*)

Despite over a hundred sorties being flown by both RNAS and RFC aircraft, only one German aircraft was shot down throughout the day. By the time fighters had caught up with the Gothas, they were some thirty miles off the coast, and this time restriction was not helped by the fact that multiple British pilots experienced gun jams at the critical moment that they tried to engage an enemy aircraft. In many cases. the guns would only fire off twenty or thirty or so rounds before becoming jammed, and whilst some issues with the guns could be rectified on the fly in certain aircraft, much of the time it meant having to return to base.

The one Gotha downed was officially shot down by Harold Kerby of Walmer RNAS Squadron in his Sopwith Pup. Returning from a patrol he saw in the distance eight Gothas being persued by Sopwith Camels from Eastchurch and decided to join in. Climbing above the enemy formation Kerby became aware of a straggler a few thousand feet below the others. He made a single diving attack directed at the front of the enemy which responded by slowly descending into the sea before violently flipping. Whilst circling the wreck a few feet from sea level, Kerby saw one of the crew members clinging onto the aircraft's tail and attempted to throw the man his life jacket. As he left, he fired some red flares from his Very pistol to try and attract the attention of some passing Destroyers so that the German airman might be rescued but unfortunately for him, they didn't understand the message.

Three of the German bombers, possibly due to damage sustained by attacking British aircraft crash landed upon arrival back at their airbase in Belgium, and the others landed safely despite being covered in bullet holes. The German crews claimed they had shot down three British fighters during the engagement, which despite hitting a number of the British fighters was in reality patently false.(28*)

Although the attack on the 12th of August was the last significant incursion over the town and surrounding area the attack had left Southend reeling in shock. In the weeks afterward the town finally procured an air raid siren but there were still concerns about its effectiveness. According to letters and articles in the local papers in the days immediately after, it seems the siren wasn't loud enough for everyone in the district to hear. One of the ideas from Pemberton-Billing (who I wrote of at some length in the previous part of this series on local aviation history) suggested having a captive (tethered) barrage balloon which could be raised in the event of attack. The idea was that the balloon would be visible throughout the entire area. The idea was not used, however.

Although Southend would remain relatively safe for the rest of the war, England's regular attacks from German bombers would continue for most of the war and as a result the patrols out of the nearby Rochford airfield would be called upon multiple times. Although the Zeppelin raids had captured the public's attention, bomber raids were much more frequent. Of the thirty three raids on Essex during the war, eighteen were perpetrated by planes and between May and August 1917, a total of eight daylight raids had taken place on south east of England. Despite improvements to the way in which fighter patrols were conducted and a steady advance in flying technology - the British were still struggling with how to deal with the regular attacks.

Following the attack on Southend, local fighter squadrons were deployed again ten days later on the 22nd of August when fifteen Gothas attempted a two-pronged attack on the south east area resulting in three of the attackers being shot down around Margate - this only a day after a botched German assault had led to the loss of four other bombers due to strong head winds.(29*) With Britain's air defences becoming more capable, daylight raids were abandoned - and although on the face of things it seemed as if the tide was beginning to turn in Britain's favour in the air war, German aircraft developers had an ace up their sleeves with the Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI heavy bomber. The R.VI had an enormous wingspan of 42.2m (compared with the Gotha's 23.7m) and could carry 2000kg of bombs compared with the Gotha's 350kg! Between 28th September 1917 and the 20th May 1918, 11 raids were conducted by these Giants with an estimated thirty tons of bombs landing on Britain; mostly on London. Despite the home defence's best efforts, not a single one of these Giant bombers were ever shot down over the UK.

The first of these Giant raids on London like so many before (and after) used the Thames estuary for navigation and three of these aircraft alongside the ordinary Gothas, travelled up and down the river as they committed an attack which cost forty civilians their lives. One of the Giants reportedly made a series of passes up and down the estuary before dropping their bombs on the Isle of Sheppey where fortunately nobody was injured.(30*)

During the night of the 30th of September 1917, the crew of the experimental Martinsyde F1 Capt. L.J. Wackett and Capt. F.W. Musson attempted to shoot down an enemy Gotha after taking off from Rochford, but weren't high enough for the guns to be effective. On the same night, Lt. F.L Luxmoore from No.78 Squadron based at Sutton's Farm (known as RAF Hornchurch throughout WWII) made a forced landing in a field somewhere in Benfleet.(31*)

On the 29th of October 1917, three Gothas set out to bomb English coastal towns but due to a combination of low cloud and high winds, two of the three bombed Calais and the third reached England, and claimed to drop their bombs over Sheerness. In reality it had scattered its bombs randomly in the fields between Southend and Burnham!(32*)

One of the victims of the local air defences was a German Gotha bomber which, after having sustained heavy damage from flak guns on Canvey on the 6th of December 1917, had attempted a landing at Rochford airfield. The craft made its controlled descent as far as the adjacent Rochford golf course, before crashing into a tree. The crew all survived and were taken captive, but the wreck was destroyed when a bungling RFC crew member picked up the aircraft's flare gun and accidentally discharged it, leaving nothing of the remaining wreckage but a charred frame by the following morning!

No.141 Squadron; the first full resident squadron at Rochford formed a short while later in January of 1918 and was made up of a number of pilots from No.61 squadron. It was short lived however, as the squadron was relocated to Biggin Hill only a month later. Captain Langford-Sainsbury (who also served in the RAF during WWII as wing commander of the reconnaissance and coastal command) was acting squadron leader after the commanding officer Babington was badly injured after crashing the airfield's first Sopwith Dolphin.(33*) No.61 Squadron also received a batch of SE5a fighter planes on loan (dubbed the 'ace maker' because of its superiority over many of the other designs at that time,) although two of the four that went up to engage fifteen Gothas in a raid that same month were plagued with engine issues.

In the same month, whilst returning from London, a German Gotha bomber was successfully intercepted by two Sopwith Camels flown by Capt G H Hackwell and Lt C C Bankes from No.44 Squadron based at Hainault Farm.(34*) Freidrich Von Thomsen, Walter Heiden and Karl Ziegler all died on impact when their aircraft came down in a field between the river Crouch and London Road in Wickford near Frierns Farm. (The area today is residential, but most likely came down between Castledon Road to the west and Louvaine Avenue to the east.) The crew were buried at St Margaret's at Downham before all German war dead were relocated to the German Military Cemetery at Cannock Chase.

Also in January of 1918, Lt Keith Muspratt who was once a member of No.56 Squadron, flew into Rochford with a German Albatross fighter plane which had been captured over in France and brought over to the UK for testing.

On the night of 16th of February a total of sixty home defence sorties were flown against five Giant type bombers which were destined for London. As one of the Germans approached London it struck a barrage balloon net causing the craft to flip violently to the right and then sideslip back to the left again. Remarkably, despite losing two of its bombs which fell on Woolich below, the Giant sustained only slight damage and continued flying! That same night, members of the British Home Defence Squadrons had problems of their own. The evening saw multiple complaints about the conduct of anti-aircraft emplacements which had been (at least from the pilots stories) ignoring recognition signals. The confusion caused by trigger happy anti aircraft gun fire had let to multiple cases of British fighter aircraft chasing one another - and one aircraft belonging to No.39 Squadron was attacked by a member of their own squadron! Another plane belonging to No.37 Squadron was also fired upon by a fellow RFC fighter whilst somewhere above Rayleigh.

Throughout 1918, the war above Britain began to wind down somewhat. One of the last significant raids took place on the 7th of March when six of the Giant bombers were sent to raid London. Sadly, one of the last significant local incidents ended in tragedy. Capt. Alexander Bruce Kynoch of No.37 Squadron and Capt. Henry Stroud of No.61 Squadron - collided with one another whilst on a night time patrol and both died at the scene. Kynoch who had taken off from Stow Maries in a BE12 and Stroud from Rochford in a SE5a, had been flying through cloud cover just north of the village of Shotgate near Rayleigh before colliding - both aircraft came down in a field which now runs parallel with the new A130 dual carriageway.

An extraordinary account exists from that night in the January 1960 issue of Essex Countryside Magazine written by a woman (then a girl) who had been one of the first at the scene of the crash.

"It is gratifying to note the interest which readers have taken in the simple propeller memorials which my brother, William Woodburn Wilson, had erected to preserve the memory of the brave pilots who collided at midnight on their return from pursuing the German raiders on London.

My brother and I were the only persons who ran to the scene of the awful crash, which occurred on our Rawreth fields, over a mile from our home, Great Fanton Hall, North Benfleet. The pilots were beyond help; indeed Captain Clifford Stroud was not found until daylight revealed his body deeply embedded in the ground some distance from his plane, and where the sundial now stands, replacing the original propeller.

While I kept watch over Captain Bruce Kynoch, whose hands were still grasping the controls, my brother went to the Carpenters' Arms to get help to carry his body.

One great pasture field on the hall side of the railway provided an ideal landing ground, and one day a famous pilot, on leave from France, landed here to bring us two memorial plaques from the RFC to place on the propellers, also a present for me; the small electric lamp with battery which Captain Kynoch had worn and with his name thereon. This was at the suggestion of Captain Fanstone, squadron leader at the Stowe Maries aerodrome where Kynoch was based.

The plaques stated their names and squadrons and that they "fell on this spot at midnight, March 7th, 1918." They also bore the following injunction: "Let those who come after see that his name be not forgotten."

At that time we owned over 1,000 acres of land between Wickford and Rayleigh, crossed by the railway and latterly by the new arterial road. When my brother sold his property he had it incorporated into the title deeds that these two small plots were not included in the sale, were still his property, and were to be for ever held sacred.

Captain Kynoch was buried in a tree-shaded avenue at Golders Green. His parents brought us a most beautifully made photo frame, constructed in the form of a thin case, holding a picture of his last resting place. On the front were inserted two silver-framed miniatures of him, one as a smiling, happy boy, the other in uniform. A plaque and the crowned wings in silver also adorn this lovely souvenir. Captain Stroud was buried at Rochford, where he had been based. His father was a professor at Armstrong College, King's College, Newcastle.

- Jean Woodburn Wilson."(35*)

The two memorials to both Stroud and Kynoch exist to this day although they certainly require some restoration. The current land owner has recently been trying to obtain permission for a rubbish burning site in the fields surrounding these memorials, and has apparently suggested moving the memorials to somewhere more accessible. (One of them is accessible via a nearby footpath but the other is surrounded by private land - the land owner is apparently creating a bit of a fuss about access.) It is my opinion that these memorials must not be moved as their positions are placed at the exact locations at which their bodies were found following the crash. If you were to move them, you may as well not bother having them at all! At least the bridge which is close to the memorials at least gives a nod to their memory as it is named Monument Bridge - although this fact is likely known only by the smallest number of daily travelers along the dual carriageway.

As the war came to a close, Rochford's military use waned. On the 4th of December, 1919, the last WWI flight from the airfield was conducted by Lt. Bromfield from No.39 Home Defence Squadron flying a Bristol Fighter - the exact aircraft with tail number 'E2581' has been on display at both IWM Duxford and Lambeth since 1923 and is still available to see today. Although the airfield officially shut down in 1920 - it obviously wasn't the end of the story. If anything WWI had simply proven the importance of air travel and its usefulness, and south east Essex still had a large part to play in Britain's aviation history.

Glimpsing some nearby coastline in the light of a sweeping searchbeam, Morgan expertly set down his BE2c on the marshes at Thameshaven (to the south of Corringham) achieving a perfect landing. The following afternoon the aircraft was flown back to Rochford.(10*) This kind of account is not uncommon for those tasked with flying night patrols. They were basically done blind with no on board radios, limited visibility and in aircraft of questionable reliability.

L19, the only Zeppelin not to make it back that night came down in the North Sea after three of its four engines had failed. It is thought that as it floundered without power, Dutch anti-aircraft fire had ruptured its gas cells. An English trawler had come across the airship a day later as she was partially submerged with sixteen of the crew members clinging on to the hull for dear life, but fearing that the German's could overpower the trawler's crew, they refused to rescue the stranded men. Subsequently the men were left to their fate, and all sixteen German crew members were eventually drowned.

L15: Zeppelin In The Estuary

|

| L15 in flight. |

Breithaupt's bad set of circumstances began as soon as she reached the English coast over Great Yarmouth as the crew was taken by surprise by the newly installed anti-aircraft batteries in the area. She was caught in the searchlights and was put under heavy fire prompting the crew of L15 to drop their ballast and climb to the height of 10,000ft. Having risen to such an altitude though, navigation was now an issue and with cloud preventing a view of the land below, the crew dropped a gondola and some 'light bombs' to help ascertain their position. (Some of the zeppelins were equipped with a gondola that could be hung hundreds of feet below the airship's hull by means of cable, and communicated with the bridge via a telephone cable.)

By 9pm L15 was passing Witham and heading towards Pitsea and after finally catching a glimpse of the Thames on the horizon, was readying themselves to follow the river to the main target of London. However the craft's engines began to fail and without any additional ballast to drop, keeping level flight was becoming an issue. Disaster struck the Zeppelin as searchlights operating out of Dartford found their quarry at around 9.40pm, prompting multiple local guns to commence firing all at once. In an attempt to escape the bombardment, Breithaupt ordered the airship to head north away from the gun batteries and in an attempt to climb higher, jettisoned the majority of bombs which thankfully landed harmlessly in a field in Rainham. After five minutes of constant bombardment however, the British guns finally did some damage as shrapnel shredded a large hole in the side of L15's hull and caused three of the gas cells to become punctured and deflate.(16*) Struggling to keep altitude she drifted towards Ingatestone where ten minutes after being struck by the Purfleet battery, where a BE2c aircraft piloted by 2nd Lt. Albert De Bath Brandon had become aware of L15 in the searchlights and in among the commotion of gunfire.

Brandon from No.19 RNAS squadron flew out of an aerodrome at Hainault Farm, and had only been

a qualified pilot for a week. Brandon carefully positioned his aircraft three to four-hundred feet above the floundering airship and dropped three ranken darts on top of her. Despite the noise of the engine and gun fire from L15's top machine gun nest which had become aware of Brandon's presence, he was adamant that he had heard the sounds of all three missiles hitting their target, but they had apparently bounced off the hull with no effect. After the first pass, Brandon became aware that he'd left his navigation lights on and hastily switched them off. It was no wonder the machine gunner on the L15 were returning fire having been provided such an easy target!

The BE2c circled around to make another attack, but whilst fumbling in the darkness to load an incendiary bomb into the launch tube, he almost overshot the target and so with the bomb now sitting on his lap, he tried the remaining darts. After a ten minute engagement, Brandon lost sight of the airship and despite flying for another hour in an attempt to catch back up with the damaged airship, was unable to find it. With mist now rolling in he set his aircraft down at the first airfield he could find at Farningham, breaking a wing and a skid in the process. Despite having his navigation lights on in the first pass he remarkably had one been hit by enemy machine gun fire three times, with one bullet hole in the wing and two in the tail.(17*)

The BE2c circled around to make another attack, but whilst fumbling in the darkness to load an incendiary bomb into the launch tube, he almost overshot the target and so with the bomb now sitting on his lap, he tried the remaining darts. After a ten minute engagement, Brandon lost sight of the airship and despite flying for another hour in an attempt to catch back up with the damaged airship, was unable to find it. With mist now rolling in he set his aircraft down at the first airfield he could find at Farningham, breaking a wing and a skid in the process. Despite having his navigation lights on in the first pass he remarkably had one been hit by enemy machine gun fire three times, with one bullet hole in the wing and two in the tail.(17*)

a qualified pilot for a week. Brandon carefully positioned his aircraft three to four-hundred feet above the floundering airship and dropped three ranken darts on top of her. Despite the noise of the engine and gun fire from L15's top machine gun nest which had become aware of Brandon's presence, he was adamant that he had heard the sounds of all three missiles hitting their target, but they had apparently bounced off the hull with no effect. After the first pass, Brandon became aware that he'd left his navigation lights on and hastily switched them off. It was no wonder the machine gunner on the L15 were returning fire having been provided such an easy target!

The BE2c circled around to make another attack, but whilst fumbling in the darkness to load an incendiary bomb into the launch tube, he almost overshot the target and so with the bomb now sitting on his lap, he tried the remaining darts. After a ten minute engagement, Brandon lost sight of the airship and despite flying for another hour in an attempt to catch back up with the damaged airship, was unable to find it. With mist now rolling in he set his aircraft down at the first airfield he could find at Farningham, breaking a wing and a skid in the process. Despite having his navigation lights on in the first pass he remarkably had one been hit by enemy machine gun fire three times, with one bullet hole in the wing and two in the tail.(17*)

The BE2c circled around to make another attack, but whilst fumbling in the darkness to load an incendiary bomb into the launch tube, he almost overshot the target and so with the bomb now sitting on his lap, he tried the remaining darts. After a ten minute engagement, Brandon lost sight of the airship and despite flying for another hour in an attempt to catch back up with the damaged airship, was unable to find it. With mist now rolling in he set his aircraft down at the first airfield he could find at Farningham, breaking a wing and a skid in the process. Despite having his navigation lights on in the first pass he remarkably had one been hit by enemy machine gun fire three times, with one bullet hole in the wing and two in the tail.(17*)

By the time the airship had reached Kelvedon Hatch, it was so low that a local machine gun nest operated by a Captain Hulton, claimed to have been able to fire up at it as it passed overhead. Struggling to stay afloat, the crew of L15 began to resort to drastic measures. As they passed over South Hanningfield, many of the heavier items were dropped overboard including machine guns, fuel tanks and the detachable gondola which upon inspection had seemed to bear the scars of Hulton's machine gun fire. The six remaining bombs on board were retained should they come across an easy target on their way back to Belgium, but the situation on board was getting dire.

By 10:25pm, the doomed Zeppelin was passing just south of Althourne, following the river Crouch out to the east, but for some unknown reason (most likely due to engine troubles) the craft began to circle between Burnham, Foulness and Southminster. Most sources for the story of L15 claim that after circling Foulness she eventually headed out into the estuary where she broke up and landed in the water just off Maldon. However that may not be all there is to the story. A small booklet published by Stephen Aylen; a local Southend town councillor for Belfairs and a historian, writes that after circling Foulness she eventually began heading south west until two of its engines failed above Rayleigh, putting L15 into a wide left-hand turn. Still struggling to maintain altitude, Breithaupt gave the order to jettison the remaining bombs. One of these bombs apparently landed on the pump of a local borehole reservoir at Oakwood in Eastwood, which at that point was one of Southend's major water supplies.

By 10:25pm, the doomed Zeppelin was passing just south of Althourne, following the river Crouch out to the east, but for some unknown reason (most likely due to engine troubles) the craft began to circle between Burnham, Foulness and Southminster. Most sources for the story of L15 claim that after circling Foulness she eventually headed out into the estuary where she broke up and landed in the water just off Maldon. However that may not be all there is to the story. A small booklet published by Stephen Aylen; a local Southend town councillor for Belfairs and a historian, writes that after circling Foulness she eventually began heading south west until two of its engines failed above Rayleigh, putting L15 into a wide left-hand turn. Still struggling to maintain altitude, Breithaupt gave the order to jettison the remaining bombs. One of these bombs apparently landed on the pump of a local borehole reservoir at Oakwood in Eastwood, which at that point was one of Southend's major water supplies.

|

| One of the machine guns thrown overboard around Hanningfield. |

By 11:55, L15 had come to a grinding halt remaining stationary above what is now the Elms public house. At just a few hundred feet up, the locals on the ground could hear the Germans shouting to one another as they struggled to get the engines back online, prompting many of the locals to begin jeering and shouting abuse up at the airmen above. As the airship remained stationary, an RFC BE2c flown by Sub Lt G. L. F. Stevens arrived on scene, but perhaps after realising the built up area below, decided not to attack. His report afterwards mentioned that he had been driven away by gunfire from the Zeppelin, but that would be pretty difficult considering the Zeppelin crew had already thrown all their machine guns overboard! The real reason as to why he didn't engage might have something to do with the fact that Steven's parents lived not too far away!

Whilst this had been going on, a runner is alleged to have alerted the local gun battery at Chalkwell park of the presence of the Zeppelin, but by time the order to engage came through the phone, the engines had roared back into action and the craft had continued on towards Two Tree Island where a local duck hunter instead gave the Zeppelin both barrels of his shotgun as she soared overhead. As she turned east out towards the mouth of the estuary, the gun batteries at Southend pier were taken by surprise and never even got a shot off - although it possible that they didn't open fire because of the low elevation.

Meanwhile, ships in the estuary were given the order over wirelesss to look out for a low-flying Zeppelin in the vicinity. A large trawler which had been converted into a makeshift gunboat called 'Olivine' did get eyes on her, and saw L15 travelling at less than 2000ft at full speed, somehow slowly gaining altitude; but the strain on the wooden structure of the airship had been too much, and the lack of the central gas cells finally broke her spine. She fell unceremoniously into the sea just off Margate and the Olivine found all but one of the crew members had survived (the radio operator had apparently died trying to scupper secret radio codes) and were taken ashore by HMS Vulture.(18*)

|

| A painting of the 'Olivine' coming across L15 |

Initially there had been a prize of £500 offered to the first crew members to successfully take down zeppelins, but given that so many men had played a part in L15's destruction, it left the issue that many men were claiming at least some partial credit. In the end, multiple medals were forged instead of the cash prize as a thank you to the multiple individuals who had had their own part to play. Whilst this story sounds great, especially from a local perspective - I must make clear that Mr. Aylen's booklet is the only written account I have come across which mentions the bombing of Eastwood and Belfairs, so please be wary before taking this story as gospel.

Home Defence Begins Organising

On the 26th April 1916 the administration of Rochford airfield was officially handed from the RNAS to the RFC, with new RFC home defence squadrons forming to counter the increasing threat of both Gotha bombers and Zeppelins. The need for proper solutions for home defence was getting quite serious as German bomber aircraft were still raiding England pretty much unchallenged in most cases.

On the 13th June 1916 fourteen Gotha bombers attacked London killing 160 people and injuring 414; the highest casualties from any bomber raid during the first world war. Not only did the bombers succeed in hitting their intended target but they did so without the loss of a single aircraft, despite the fact that the British had put up a grand total of 92 aircraft to try and intercept the Gothas, and of the 11 British pilots who fired their guns in anger that day, only five were in any sort of effective range. In fact the only loss throughout the day was a British gunner!

A cabinet meeting in the British Government following the attack agreed that the overall strength of the flying service in the war should be doubled and that home defence should be taken much more seriously. Hugh Trenchard the commanding officer of the RFC, argued that home patrols would be very costly in terms of both machines and man power which was otherwise required on the Western front. He insisted that any units loaned from from the Western Front must be back by the 5th of July. Field Marshall Haig of the British Expeditionary Force was warned on the 15th of June that one or two of his fighter Squadrons would be required, and that the decision was confirmed by the Cabinet War Policy Committee meeting on the 20th June attended by both Haig and Trenchard, with the order to send back Squadrons sent later that day. No.56 Squadron flew its SE5a's back to England the following day, with their A flight operating out of Rochford, and B and C flight operating from Bekesbourne in Kent. As it happens, they never were sent back to the Western Front, as they were still very much required on the home front!(19*)

On the 13th June 1916 fourteen Gotha bombers attacked London killing 160 people and injuring 414; the highest casualties from any bomber raid during the first world war. Not only did the bombers succeed in hitting their intended target but they did so without the loss of a single aircraft, despite the fact that the British had put up a grand total of 92 aircraft to try and intercept the Gothas, and of the 11 British pilots who fired their guns in anger that day, only five were in any sort of effective range. In fact the only loss throughout the day was a British gunner!

A cabinet meeting in the British Government following the attack agreed that the overall strength of the flying service in the war should be doubled and that home defence should be taken much more seriously. Hugh Trenchard the commanding officer of the RFC, argued that home patrols would be very costly in terms of both machines and man power which was otherwise required on the Western front. He insisted that any units loaned from from the Western Front must be back by the 5th of July. Field Marshall Haig of the British Expeditionary Force was warned on the 15th of June that one or two of his fighter Squadrons would be required, and that the decision was confirmed by the Cabinet War Policy Committee meeting on the 20th June attended by both Haig and Trenchard, with the order to send back Squadrons sent later that day. No.56 Squadron flew its SE5a's back to England the following day, with their A flight operating out of Rochford, and B and C flight operating from Bekesbourne in Kent. As it happens, they never were sent back to the Western Front, as they were still very much required on the home front!(19*)

In September of 1916 the RFC's 37th Squadron formed and was also tasked with the defence of Essex. Their headquarters was based out of Woodham Mortimer, but most flights operated out of Goldhanger near Maldon and Stow Maries, but they also had a permanent flight operating out of Rochford. Incidentally, the airfield Stow Maries (near South Woodham Ferrers) still exists to this day as a true to life WWI airfield and museum, equipped with reproduction WWI fighter aircraft and still has an active runway for flying displays.

The need for more aircraft both at home and on the Western front had understandably led to a shortage of aircrews. With new pilots being pushed out onto frontline duty with just an average of fifteen hours flying experience, the average life expectancy of any new flyer was just eleven days. In order to keep the RFC and RNAS flying, more training squadrons were required, and one of these training squadrons, the night training reserve squadron No.11 RS (later renamed No.98 Depot Squadron) formed at Rochford airfield during the February of 1917. Four months later another training squadron formed at Rochford during the summer, No. 99 (D) Squadron, but were soon moved to Retford near Sheffield after some confusion began between the various squadrons now based at Rochford and the serial numbers involved. (22*)

One of the pilots to train at Rochford airfield was Giles Turberville, who later came back to the airport after WWII had ended as the public relations officer for British Air Ferries. BAF was an airline operating out of Southend in the sixties which enabled a roll-on car ferry service to Europe. Its hard to imagine the sense of progress that generation had considering flight and technology in general between the periods of the first world war and the and fifties and sixties!(23*)

The need for more aircraft both at home and on the Western front had understandably led to a shortage of aircrews. With new pilots being pushed out onto frontline duty with just an average of fifteen hours flying experience, the average life expectancy of any new flyer was just eleven days. In order to keep the RFC and RNAS flying, more training squadrons were required, and one of these training squadrons, the night training reserve squadron No.11 RS (later renamed No.98 Depot Squadron) formed at Rochford airfield during the February of 1917. Four months later another training squadron formed at Rochford during the summer, No. 99 (D) Squadron, but were soon moved to Retford near Sheffield after some confusion began between the various squadrons now based at Rochford and the serial numbers involved. (22*)

One of the pilots to train at Rochford airfield was Giles Turberville, who later came back to the airport after WWII had ended as the public relations officer for British Air Ferries. BAF was an airline operating out of Southend in the sixties which enabled a roll-on car ferry service to Europe. Its hard to imagine the sense of progress that generation had considering flight and technology in general between the periods of the first world war and the and fifties and sixties!(23*)

Despite the best intentions being made to bulk up the strength of the home defence squadrons in terms of numbers, the limitations of the machines the RFC were using were still blaringly oblivious. Up until this point in the war, most of the night fighter squadrons consisted of slightly modified reconnaissance aircraft such as the BE2d and BE12s, and their performance was generally atrocious for the role they had been designated. As an example, on the 25th of May 1917, sorties flown out of Rochford to intercept German Gotha bombers almost ended in disaster; Captain Cooke, the commander of No.37 Squadron's 'C flight' which operated from Rochford, spotted the silhouette of passing Gotha bombers as he took off in his BE.12a but by the time he had climbed above cloud level at 5000ft, they were completely out of sight. Determined to find them again he pressed on heading south-west and had just reached 13,000ft when his engine suddenly burst into flames. The fire was extinguished by Cooke's ingenious execution of a sudden tail slide, but after turning in such a violent manner to get the fire under control, he then became aware that the aircraft centre-section and wings were swaying about in an alarming fashion.(20*)

In the report filed by Cooke shortly after landing, he wrote "[the plane's fragility] Evidently owing to the inability of the machine to withstand rough usage in an air fight. If I had been on a fast climbing scout I would be able to keep in touch with the hostile aircraft. The BE12a, will not climb above 14,000ft and at that height it is impossible to do a sharp turn without losing about 500ft, owing to the fact that the machine has no [power] reserve, and it is only just able to keep that height."

Of the four flights that took off from Rochford that night, two of them had ended in engine failure.

In the report filed by Cooke shortly after landing, he wrote "[the plane's fragility] Evidently owing to the inability of the machine to withstand rough usage in an air fight. If I had been on a fast climbing scout I would be able to keep in touch with the hostile aircraft. The BE12a, will not climb above 14,000ft and at that height it is impossible to do a sharp turn without losing about 500ft, owing to the fact that the machine has no [power] reserve, and it is only just able to keep that height."

Of the four flights that took off from Rochford that night, two of them had ended in engine failure.